Wine is a complicated matter. A rich culture comprised of centuries of history and tradition resulting in the diverse and intricate world of terroirs, grape varieties and styles that we know today. It is in all its refined complexity, however, not alone.

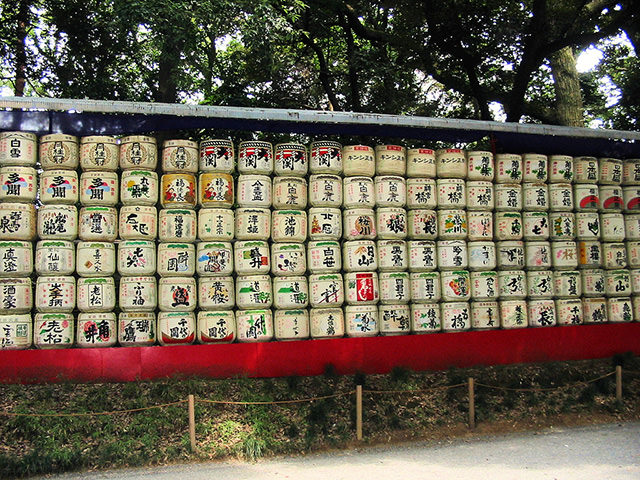

The world of sake is notoriously elaborate. It takes great skill and effort to produce it, as well as to study it. It’s impossible to summarize all the different styles and variations in one article; but here are the basics.

Sake is an alcoholic fermented rice beverage from Japan. Yet sake is a generic Japanese term for “alcohol”. In Japan the rice wine is called “nihonshu”, meaning alcohol from Japan. For the sake of convenience and convention we’ll stick to the term sake.

The main ingredients in sake are rice, water and sometimes brewer’s alcohol. It’s often referred to as rice wine but that’s a bit of a misnomer. The production process is actually closer to that of beer than that of wine.

With so little ingredients it speaks for itself that the quality of the ingredients are of great importance. Over 80 types of sake rice are grown in Japan and a lot of breweries will be near a natural spring. The quality of the water is of great importance since certain minerals have certain effects on the brewing process and ultimately on the character of the sake.

The first step in making sake is polishing the rice. Prior to fermentation the rice kernel has to be polished to remove the outer layer of each grain, exposing its starchy core.

To produce good sake, the rice is usually polished to between 70% and 50%, meaning 30% – 50% of the kernel is removed.

After this the rice is washed, soaked and cooked. A mold is added to allow the rice to ferment for a period of 5 to 7 days. Later on more water and yeast cultures are added after which more cooked rice, fermented rice and water are added to the main mash. This mixture is then finally fermented for 2 to 3 weeks. This type of fermentation (explained here very roughly) is called parallel fermentation. It allows the sake to have a higher alcohol content without the use of distillation.

When the fermentation has finished the sake is extracted from the solid mixture through a filtration process. For some types a little brewer’s alcohol is added before pressing and filtration to extract flavors and aromas that would otherwise remain behind.

After the brewing process, sake is usually matured for a period of 9 to 12 months before it is ready for consumption.

As mentioned earlier there is a vast number of different types of sake. Here are the major ones:

Junmai

Junmai is sake made from pure rice, which means that no other additives such as sugar or alcohol are used. Unless a bottle says “junmai” it will have added brewer’s alcohol and/or some other additives. While junmai sounds like a good thing, other sakes that are not junmai can be of equal quality. Skilled sake brewers use certain additives to achieve better flavor profiles and enhanced aromas.

Additionally, the junmai classification means that the rice used has to be polished to at least 70%. Junmai sake usually has a rich and full body with an intense, slightly acidic flavor.

Honjozo

Honjozo is similar to junmai as it uses rice that has been polished to at least 70%. The difference lies in the addition of a small amount of brewer’s alcohol, which is added to smooth out the flavor and aroma of the sake.

Ginjo & Junmai Ginjo

Ginjo is a premium type of sake that uses rice that has been polished to at least 60%. Next to that it is brewed using special yeast and fermenting techniques, resulting in a light flavor and fruity aroma.

Junmai ginjo fits both junmai and ginjo requirements, premium sake without any additives.

Daiginjo & Junmai Daiginjo

Daiginjo comes from the above mentioned ginjo and the Japanese word “dai”, meaning big. It’s more premium than ginjo and thus requires precise brewing methods and uses rice that has been polished down to 50%. These expensive sakes have extremely complex flavors and aromas.

Junmai Daiginjo is simply Daiginjo without additives.

Futushu

The opposite of the above, futushu is table sake. The rice is usually barely polished and a lot of brewer’s alcohol and other additives are used. The equivalent of 7/11 wine.

Shiboritate

Most sake is matured for a period of 6 to 12 months before consumption. This settles and mellows out the flavors. In contrast, shiboritate sake goes directly from the presses into the bottles and out to the market. It’s wild and fruity character is either loved or hated.

Nama-Zake

Sake is pasteurized twice, once after brewing and once more before shipping. Nama-Zake is unpasteurized and has to be refrigerated to be kept fresh. It often has a fresh, fruity flavor with a sweet aroma.

Nigori

Although most sakes are clear liquids, nigori is cloudy with tiny bits of rice floating around in it. This is the result of a coarse filtration. It’s sweet and creamy and can range from silky smooth to thick and chunky.

Jizake

Jizake simply means local sake. You’ll be hard pressed to find this outside of Japan. Yet in Japan we recommended you try it. Since it’s produced locally it usually goes well with a region’s cuisine. On top of that it’s usually very fresh and affordable.

One more important matter needs some attention. It’s a misconception that sake is always consumed warm. Sakes can be drunken cold, at room temperature and hot. Every sake is different and deserves a different treatment.. It is up to the character of the sake and what you like. If in doubt, ask the shop or restaurant for advice.

Although this seems like a lot of information already, this is only the tip of the iceberg. Becoming a master in sake is as hard as becoming a sommelier and can require years of studying and tasting. We’ll stick to the latter.

Cheers.

[Article by Alexander Eeckhout]

0

0