The article originally appeared on The Washington Post on January 6

Behind the picturesque rows of grapevines at vineyards around the world, winemakers are bending the truth. It’s not the sort of thing most wine drinkers would have noticed, because it’s happening behind the scenes, before bottles are shipped out, and it’s tough to tell by taste. But it’s hard to imagine anyone would appreciate it.

Many winemakers have been a little loose with the information shared on their labels. Not with the region, vineyard, year and varietal, which people — both expert and not — look to when buying wine, but with the alcohol content, which they have been misreporting on bottles for decades.

The percentages reported on bottles aren’t the precise measurements consumers likely believe them to be. A number of factors, including tastes, expectations, associations, rating systems and even international tax laws appear to be nudging winemakers to round the alcoholic kick of their respective wines up or down a notch on labels in ways that might make the bottles more attractive to prospective drinkers. And the problem is widespread.

“The errors, whether deemed ‘small’ or ‘large,’ are systematic,” said Kate Fuller, who teaches agricultural economics at Montana State University.

This past fall, Fuller, along with a team of researchers that included Julian Alston, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics of the University of California at Davis, and James Lapsley, a retired professor who has written and researched extensively about wine, set out to test two theories. The first was something experts have been warning about for some time: Wines, for various reasons, have been getting more alcoholic. The second was something else: Winemakers have been inaccurately reporting the alcoholic contents of their wines.

The team dusted off data from the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, which oversees and tests all wine imported for sale in Ontario, Canada. The sample included more than 127,000 wines (roughly 80,000 of them red, 47,000 of them white) imported over the eighteen years between 1992 and 2009. And it told an interesting tale.

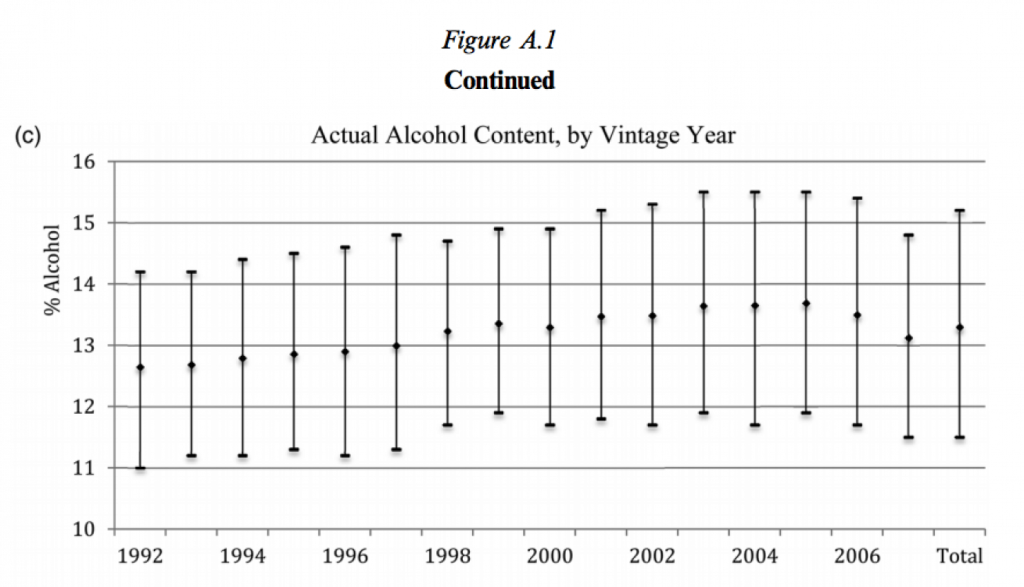

As suspected, wines are getting boozier. On average, they were about a percentage point stronger in 2009 (13.8 percent alcohol by volume) than they were in 1992 (12.7 percent). “There was growth in alcohol percentage in every country,” the researchers wrote. The chart below shows the worldwide increase over time. Some suspect that global warming and the rising heat index, which could be altering an already fussy production process, are to blame. Michael Kaiser, who is the director of public affairs for Wine America, a national association that represents American wineries, says the sugar content of the grape, which in turn affects the alcohol content of the wine, is altered by climate. “In some places, winemakers have had to change the types of grapes they’re growing to adjust.”

Some suspect that global warming and the rising heat index, which could be altering an already fussy production process, are to blame. Michael Kaiser, who is the director of public affairs for Wine America, a national association that represents American wineries, says the sugar content of the grape, which in turn affects the alcohol content of the wine, is altered by climate. “In some places, winemakers have had to change the types of grapes they’re growing to adjust.”

But Fuller and the team believe it has less to do with external factors than it does with the practices of the actual winemakers. “Our findings lead us to think that the rise in alcohol content of wine is primarily man-made, even if as an unintended consequence of choices made by grape growers and winemakers,” they wrote.

Kaiser, for his part, admits that evolving tastes might be playing a role, too. “The palate of the consumer is probably partly to blame,” he said. “Americans tend to like sweeter beverages. So winemakers might be leaving the grapes on a little longer to get a wine that is a little fruitier and has a higher alcohol content.”

Many winemakers, however, don’t appear to want to let consumers know about the trend. In fact, they seem to be going out of their way to conceal it. The analysis uncovered a sizable discrepancy between the alcohol content reported on bottles and the actual alcohol amount observed during testing, largely due to systemic underreporting.

It’s legal. In the United States, wines with 14 percent alcohol by volume or less are allowed to have a range of 1.5 percentage points from the amount stated on the bottle. In Australia and New Zealand, it’s 1.5 percentage points, too. And in Europe, the permitted range is half a percentage point, which is about as stringent as it gets.

But Fuller says it is no less disturbing. “I thought there would be some discrepancies between the actual and reported [alcohol contents], but I didn’t expect so many would be underreporting,” said Fuller.

Nearly 60 percent of the more than 100,000 bottles observed had more alcohol by volume than their bottles would lead people to believe, while just a shade over 20 percent had less.

On average, wines around the world tended to understate the alcohol percentage by volume by 0.15 percentage points. New World wines (red and whites from the United States, South America, Australia, etc.), underreported by closer to 0.2 percentage points on average, while Old World Wines (largely those from Europe) tended to understate it by just over 0.1 percentage points. The wines from Chile, Argentina, the United States and Spain, meanwhile, which underreported alcohol content by 0.27, 0.24, 0.23, and 0.21 percentage points respectively, carried the least accurate labels.

These discrepancies likely won’t make much of a difference — in terms of health or driving ability — if you are having a single glass of wine, but could if you’re having more, Fuller warned. What’s more, they’re averages — meaning that many wine bottles have been underreporting the alcohol percentage they contain by a good deal more. In the study, the researchers used choice words to describe what they observed: “substantial, pervasive, systematic errors in the stated alcohol percentage of wine.”

Although it’s hard to pin down the precise reasons for the prevalence of these inaccuracies, there are a few things that are likely at play.

There is, for one, something practical: taxes. In the United States, for instance, wines with more than 14 percent alcohol by volume are taxed at a higher rate (the federal excise tax increases by $0.50 per gallon for those above that threshold). Bulk winemakers, especially those selling some of the cheaper wines available, might be underreporting the alcohol content of their offerings in order to avoid the added tax, since their customers are more price-sensitive.

This quirk has led some to question whether it might be reasonable to change the definition of table wines, which have less than 14 percent alcohol by volume, especially given the broader increase in the alcohol content of wines.

“Maybe it’s time for the government to reevaluate the alcohol levels for tax reasons,” Kaiser said.

But it’s a matter of tastes, too. People, as well as experts who rate wines, expect a certain narrow range from specific varietals (more, for instance, from a Cabernet Sauvignon, which is heavier, than a Pinot Noir, which is lighter), and winemakers, rather than shunning this desire entirely, cater to it by tweaking their labels.

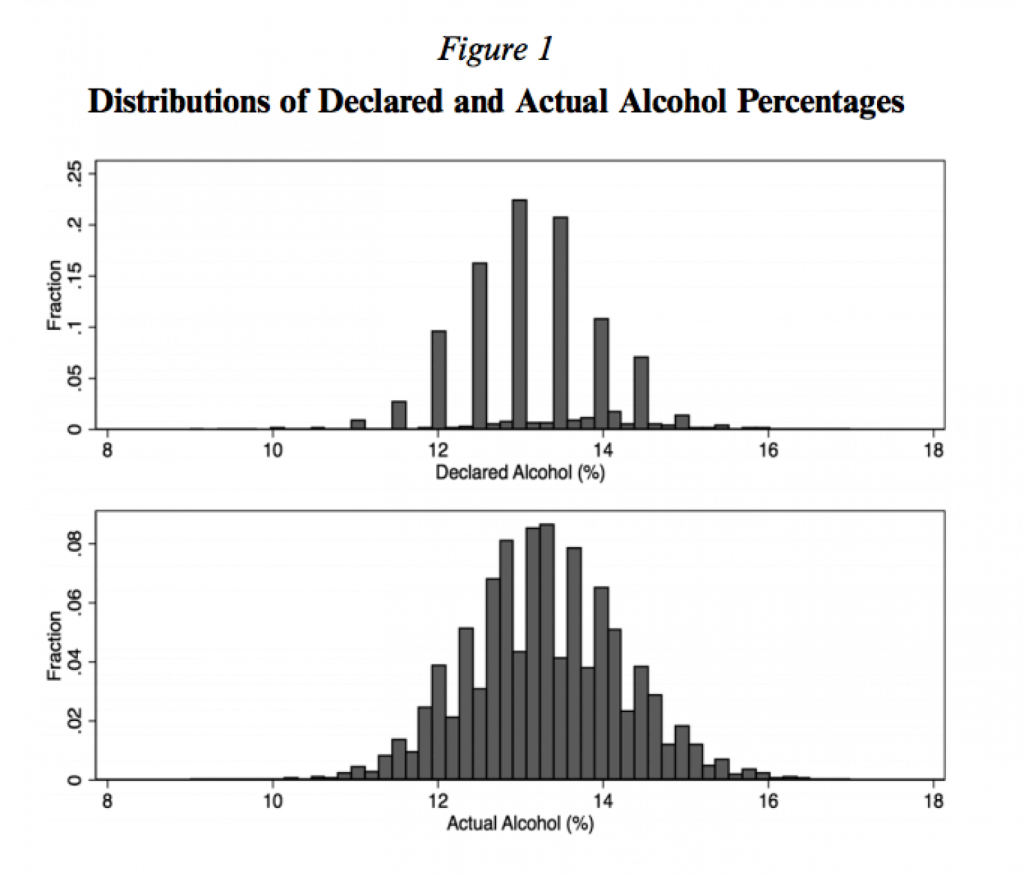

A quick look at the distribution between the declared and actual alcohol percentages shows how this affects the greater wine landscape. Notice how the wines more or less all fall into one of six declared percentages (in the chart on the top, below) but many more actual percentages (in the chart on the bottom, below).

That right there is winemakers bundling their wines into “desired” alcohol contents, rather than actual ones. Fuller and the team point out that this is likely deliberate, since wineries must know the actual alcohol content of their wine given how easy and inexpensive it is to measure it with precision today.

“I have spoken to many winemakers about this question over the past five years or so,” said Alston, who co-authored the study. “Let me say this: I would expect most winemakers to have a fairly precise idea of the alcohol content of the wines they make.”

At the heart of the discrepancy, however, is a funny little tug of war wine drinkers are forcing producers to partake in. People — on the whole — tend to favor wines that are less alcoholic. This alone means that, all things equal, rounding alcohol percentages down is better than rounding up (and, of course, not rounding at all). But it’s being exacerbated by a concurrent demand for wine with more intense and ripe flavors.

Consumers want “wines with ‘bigger’ or fuller flavors, but they do not want (or at least, do not want to know about) the higher alcohol content that typically comes with those attributes,” Fuller said.

So winemakers have made do by giving people what they want — wines with bigger bodies — and hiding from them what they don’t — the extra alcohol that comes with it. And it’s hard to see why that would stop, so long as it’s legal, and effective, and preferences don’t change. Well that, and people don’t find out about the little fibs.

“What remains to be resolved is why consumers choose to pay winemakers to lie to them,” the researchers wrote.

0

0